A new book that traces the early history of South Dakota farm tractors features several stories with strong local ties to Marshall County and the town of Eden.

Among the stories in “Grandpa’s Tractors,” written by former Public Opinion Farm Editor Chuck Cecil of Brookings, is that of Joseph Renshaw Brown, a trader and inventor who established a trading post at Eden, Dakota Territory, in 1846. The village, located in what is now Marshall County, was one of the earliest settlements in the area.

Brown’s remarkable life began in 1819, when he became a bugle boy at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Later, as a civilian, he assisted officials at Fort Wadsworth—now Fort Sisseton—in meetings with Native Americans in the territory. His wide-ranging career included service as a trader, entrepreneur, and innovator.

By the mid-1800s, Brown had become fascinated with the potential of steam power to move freight and goods across the rugged Dakota landscape. He began experimenting with steam traction engines that could be used to haul supplies to territorial forts and Native American villages. In the 1860s, he invented a steam-powered machine he called a “wagon steamer” and later improved it to create a steam traction tractor. Brown named his machine the Mazomanie, a Dakota Sioux term meaning “walking metal,” likely chosen to honor his Native American mother.

Brown also established the town of Browns Valley, Minnesota, which bears his name. His inventive spirit and early work with steam-powered machinery mark him as one of the pioneers of mechanical agriculture in the upper Midwest, decades before tractors became a common sight on farms.

Cecil’s “Grandpa’s Tractors” explores this experimental era from roughly 1890 to 1930, when inventors across the Dakotas and the Midwest were trying to determine what a tractor should look like and how it should work. The book highlights the transition from horse-powered farming to the machines that reshaped agriculture.

Cecil said his work covers a time “when no one really knew what a farm tractor was supposed to look like or do for the farmer.” He added that the book details how the change from horses to internal combustion tractors was gradual but inevitable.

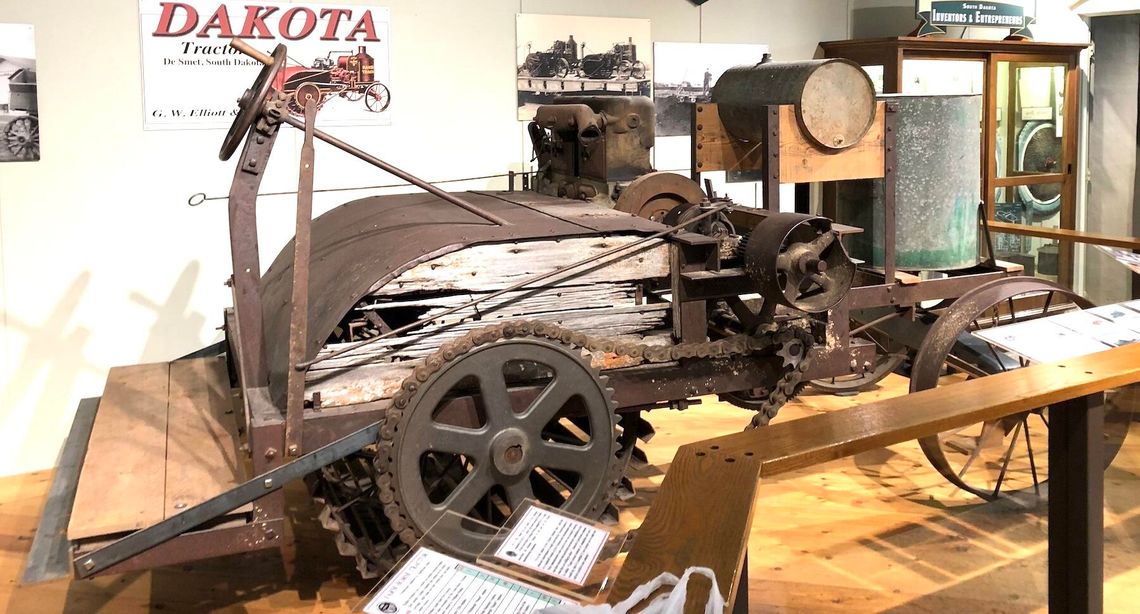

One of the key South Dakota inventors profiled in the book is Rev. George Washington Elliott of DeSmet. In 1908, Elliott and his son Paul built the Dakota tractor, one of the state’s earliest motorized farm machines. Elliott, a minister and inventor, created his tractor while simultaneously leading his congregation at the Church of Christ in Brookings.

Before his foray into tractor design, Elliott had already earned a reputation as a successful inventor and evangelist. He designed and sold windmills in the DeSmet area during Dakota Territorial days. Known for his eloquence and powerful preaching, Elliott became a minister for the Church of Christ in 1904, beginning his work in Brookings.

Elliott was born in Wisconsin in 1849. After his parents divorced and his mother died, he was raised in Owatonna, Minnesota, by an older brother. In 1883, he moved to DeSmet, Dakota Territory, while installing windmills on area farms and decided to make the community his home.

By 1908, Elliott had turned part of his DeSmet barn into a small assembly line where he built his new tractor. The four-cylinder, 22-horsepower machine featured a large, five-foot-wide cast-iron drum at the rear that propelled the tractor forward. Steering was managed by two small front wheels, while the operator stood on a wooden platform behind the machine. Although the tractor could pull four plows or eight loaded wagons, its cumbersome rear drum made it difficult to maneuver and limited its usefulness in the field.

Despite these shortcomings, Elliott’s early models generated local interest. He continued to manufacture and sell the Dakota tractor even after he was assigned in 1910 to establish a new Church of Christ congregation in Huron. The DeSmet News urged townspeople to help keep the manufacturing operation in the community, noting in 1914 that “DeSmet will not receive any appreciable benefit from the factory for a long time if he is forced to work on his capital alone.” However, local investors did not materialize.

About 20 tractors were made in DeSmet before Elliott accepted an offer from Watertown businessmen who provided factory space and financing. In 1918, Elliott joined with the Pope-Wheelock Manufacturing Company to form the Farm Tractor Company, which continued producing the Dakota tractor—sometimes called the Elliott tractor—for several years.

By 1922, however, the venture had failed, and the Watertown Public Opinion reported that the Farm Tractor Company had been “sold for back taxes.” Like many other early tractor companies of the time, the Dakota tractor disappeared as the market consolidated around larger national manufacturers.

What is believed to be the last surviving Dakota tractor was purchased at a Groton farm sale in 1914 by brothers John and George Kuntz, who farmed near Groton. The machine had been exhibited at the South Dakota State Fair in Huron the previous year. The Kuntz brothers rarely used it due to its limited practicality, but they kept it stored behind their barn for nearly 90 years.

In 2003, Bob Kuntz of Aberdeen, the son of co-owner John Kuntz, donated the family’s old Dakota tractor to South Dakota State University’s Agricultural Heritage Museum in Brookings. When it arrived, the tractor was missing its engine and the large cast-iron drive cylinder, which had been collected during a World War II scrap metal drive.

Both Elliott’s Dakota tractor and another early South Dakota-made tractor, the Farm Horse built by William Mielke of Hartford, are now on display at the SDSU Agricultural Heritage Museum.

Cecil’s book captures the stories of these and many other inventive machines from the late 19th and early 20th centuries—odd-looking contraptions that helped lay the foundation for modern agricultural equipment. “Grandpa’s Tractors” serves as both a historical record and a tribute to the ingenuity of the people who shaped South Dakota’s farming heritage.

The book is available for purchase at the Agricultural Heritage Museum, Allegra, and the Brookings Book Company. Copies may also be ordered by mail for $20, which includes tax and shipping, by sending payment to Tractors, P.O. Box 872, Brookings, SD 57006.